Words Tom Southam

Images James Jubb

I sent a screenshot from the Tour of Southland to a colleague the other evening. Now, admittedly, it was 9pm UK time, and 10pm where he lives, but I was still surprised by his response; “What are you watching that for?” My question was, why aren’t you watching it?

The thing is, I love the Tour of Southland. I’ve followed it quasi-religiously every year since I discovered some race coverage on YouTube one very early (and quite jet-lagged) morning in Melbourne, a few years ago.

My (perhaps) outsized interest in what is a relatively small race (in the grandest of schemes of things), was highlighted to me an hour or so later the same evening when I texted another colleague about a rider I saw performing well. His reply: ‘It seems like every bloody year you flag up a rider at the Tour of Southland.’

Whilst not entirely true – it’s not far off.

It reminds me of when I would excitedly sit down before dinner each night in July to watch the Channel 4 coverage of the Tour de France.

In many respects, the Tour of Southland is a long way from the World Tour, and I am not the guy who spends hours trawling the results and shaky footage of amateur races to discover new talent. I know that a lot of the riders in the race don’t even have any thoughts towards a career on the road in Europe. But truth be told, I’m not watching it for that.

There is something about a race that people are so proud of, that really appeals to me. I can talk to any rider from New Zealand about their experiences there – no matter what heights they get to in their own professional careers, and they all hold the race in the same high regard and all, to a man, of course refer to Southland with the title; ‘The Fourth Grand Tour’.

I’ve chatted to Tom Scully about the race on many a team bus ride to the start or finish of a major World Tour race. I’ve also started tracking the careers of the riders I’ve seen racing there with the same kind of zeal that a junior coach would his young charges when they go off into the big wide world.

James Oram, James Piccoli, Aaron Gate and Michael Vink are all riders who at some stage I’ve had to mention in a strategy meeting at work.

‘This guy can be good today.’

‘Who is he? I don’t know him.’

‘Ah! He won Southland… he can definitely ride a bike.’

In many ways, Southland reminds me of Ireland’s Rás. The Rás is another legendarily tough week-long race (where the weather also happens to be what you might describe as ‘patchy’ at best). Like Southland, the Rás peloton is also made up of a mixture of young hopefuls and local riders, for whom just being a part of and completing the race is the real goal.

Both races have a mystique that I can only think is born out of respect for the race at the pointy end, but also from the local’s deep affiliation to the race.

I think there is a lot to be said for a race that you can go and do – even if you have a job or kids, or you’re over forty. It is quite cool that the equivalent of a Sunday league cricketer can go and rub shoulders with the Trent Boult of the situation. There is also one more detail that the races share, and that is how hard the racing is. The racing is hard but not in the sense that Jumbo Visma are there riding so fast that the entire peloton is happy just to be in Wout Van Aert’s draft for as long as possible. Instead, the racing is hard in an unrefined and less sophisticated way than the (often predictable) top-flight races.

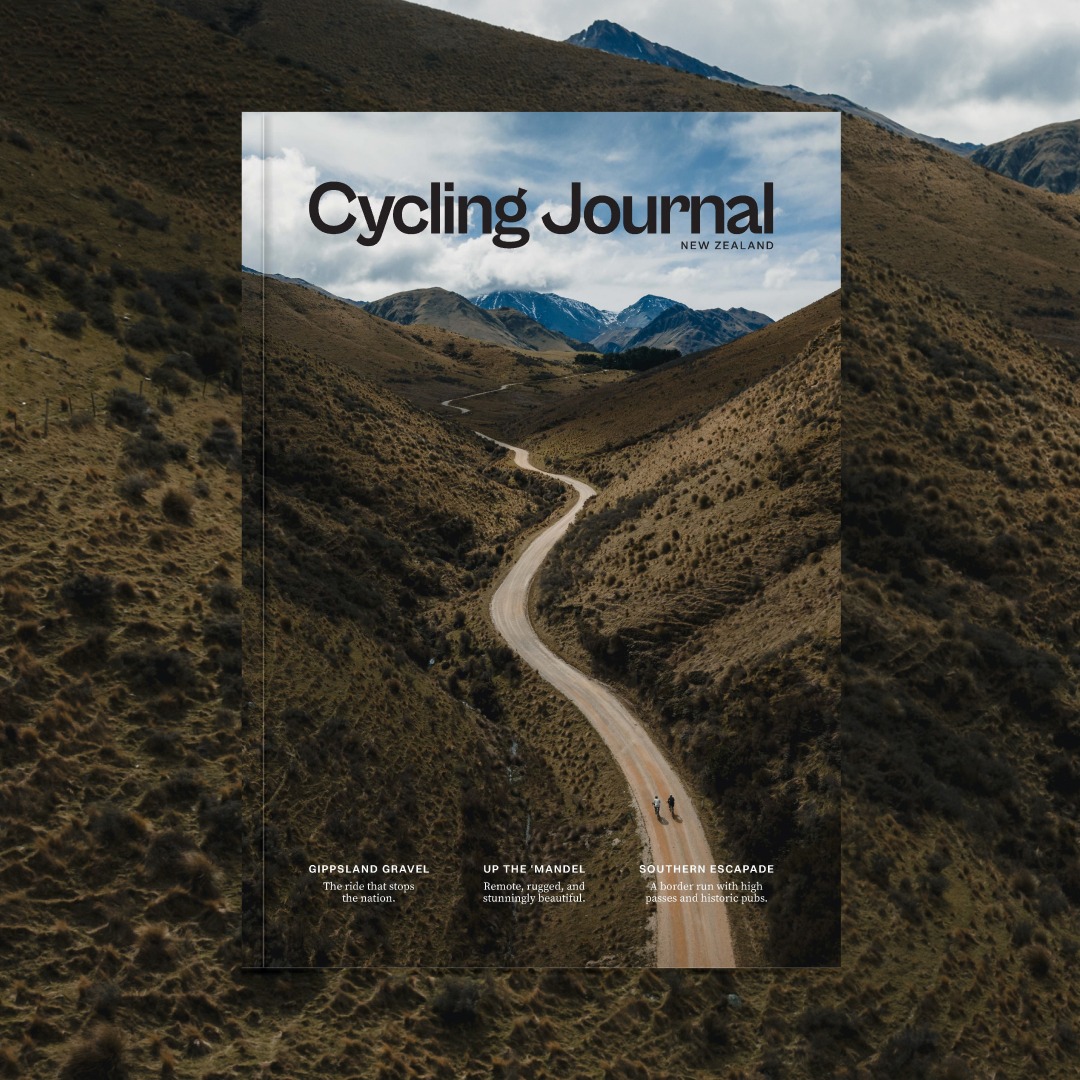

From the moment the flag drops, the attacks start and keep going. It is totally unscripted and unselfconscious racing. What is more, in Southland especially, the terrain is open and unforgiving in that you can pretty much always see quite a long way into the distance, so the temptation for another three or four riders to try to jump across any gap to a break must be huge, hence, I guess, all the hammering along. And, when the wind blows, well… that looks so hard it makes me glad I’m in another time zone.

While I’ve ridden the Rás – hence my affinity towards it – I’ve never ridden Southland, directed there, nor even (shamefully) set foot in New Zealand. What I have come to discover (after some reflection) is that I am as enamoured by the coverage of the race as much as I am the race itself.

In my opinion, the best races may not be the biggest or most important on the calendar, but they do have these things in common: a genuine connection to their public and a sense of prestige created by the promotion of the race.

The very first time I started watching the neatly packaged – and promptly uploaded – coverage on YouTube I got a warm feeling about the race. The highlights show, I realise, is just perfect. From the historic opening credits to the interviews inside sports halls or outside vans at the start line, then cut to cheering school kids in the neutral before the inevitable attacks that go nowhere at the start of each stage. It’s all just great, because there is a real flavour of the race and you start to pick up on not only what the race is, but what it means.

The jewel in the crown is the commentators’ diligent work simultaneously explaining the race on a high level to the initiated, and in a way that the non-cycling public can follow.

It reminds me of when I would excitedly sit down before dinner each night in July to watch the Channel 4 coverage of the Tour de France. Thirty minutes of Phil and Paul gently taking us through the action of the stage in the Tour, mixed with images of chateaux and mountain vistas, plus the odd bit of local trivia.

A show like this is proof that cycling coverage doesn’t need to be flag to finish line, nor have on bike footage interspersed to dramatize the action. What makes a race fun to watch is a well-packaged narrative, some action – of course – and insight into the race, mixed in with plenty of shots of The Remarkables (or whichever countryside the producer wants to highlight).

Cycling is a sport that was born to entertain – and sell newspapers. The links between press and media coverage and the racing itself are inexorable.

It’s a fun fact that I often repeat when things are getting too serious at work – that most people who watch the Tour de France on TV each year are there for the scenery. A bike race should be a package, something that is a sporting spectacle that also promotes the area that the race is moving through.

Cycling is a sport that was born to entertain – and sell newspapers. The links between press and media coverage and the racing itself are inexorable. It is why our sport manages to continue to exist, both in terms of money coming in, and participation. The one thing that cycling has is how much ground a race can cover, and what an advert this can be for the sport and a country or an area.

If you present the race well – no matter the level – people will want to follow it, both from their homes and from the side of the road. You need to get the schoolkids out to cheer, but you also need people to fire up YouTube on the other side of the world and think, ‘actually, I wouldn’t mind going to Queenstown’.

In my opinion, the best races may not be the biggest or most important on the calendar, but they do have these things in common: a genuine connection to their public and a sense of prestige created by the promotion of the race.

It’s why I have a real affinity to these types of races, and why I will always be tuning in to watch the Tour of Southland, and probably also why I will continue bugging anyone who’ll listen to me talk about it.