Words Lester Perry

Images by Lloyd Wright

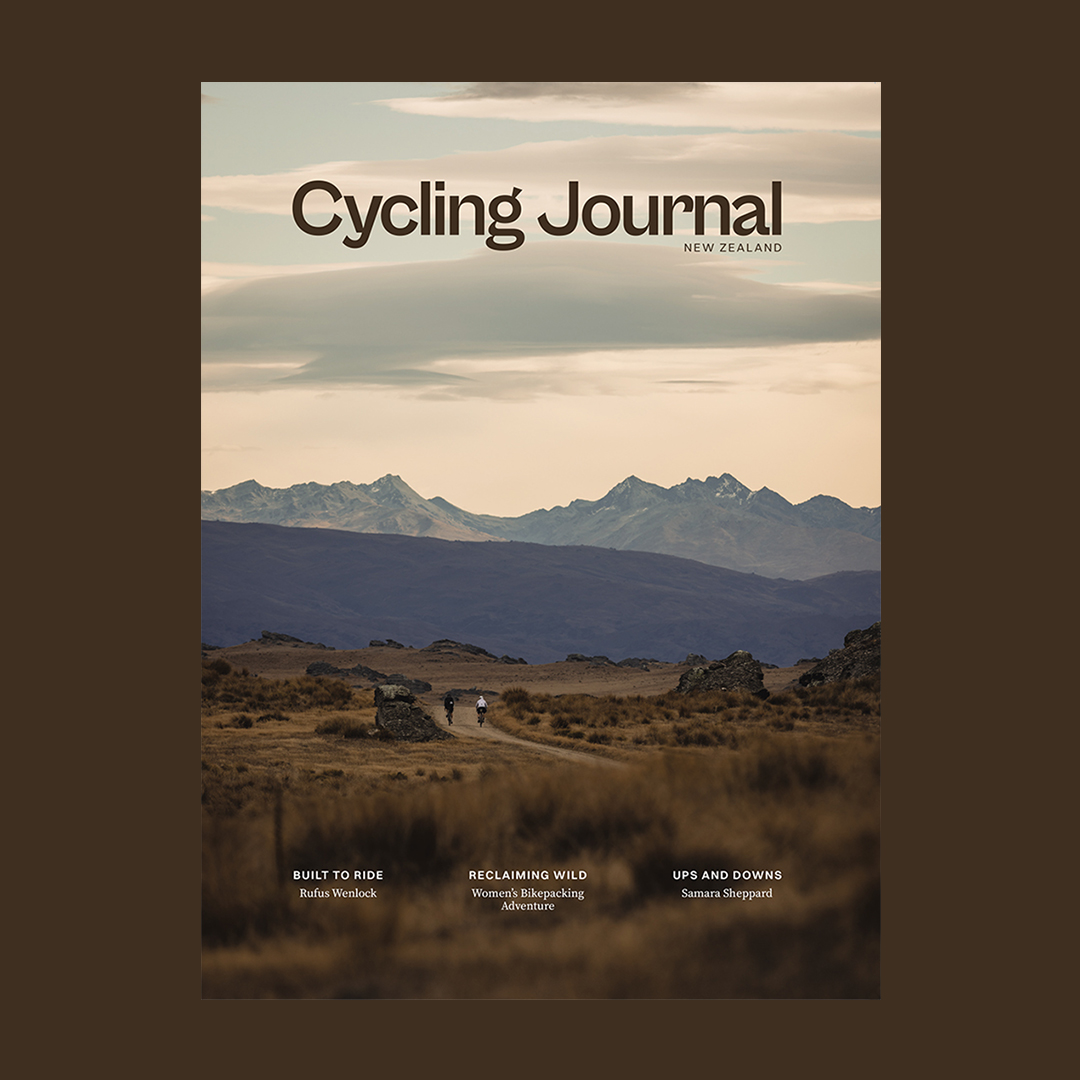

The google dictionary definition of “Trust” is: Believe in the reliability, truth, or ability of. All things Rufus Wenlock would have to place confidence in when crafting the bike he would ultimately ride to third place at the Silk Road Mountain Race (SRMR) 2024.

He’d have to trust in his ability to create a steed that was up to the task; trust that his knowledge in design, geometry and handling was truth; and trust in his ability to weld tubing together in a fashion that would be strong enough to withstand the beating it would take.

JUST DAYS BEFORE DEPARTING FOR SRMR, RUFUS WAS PUTTING THE FINAL TOUCHES ON HIS BIKE; NOT HIS BAG SETUP OR COMPONENTS, BUT THE LITERAL HEART OF THE BIKE: ITS FRAME.

This was all Rufus’ work, from design to construction and paint. Dubbed ‘Proto type-2’, this fresh build was about to take him on a 1938km adventure through the mountains of Kyrgyzstan, and help score him third place in what is arguably one of the toughest off-road ultra bikepacking races.

Rewind the clock and Rufus’ formative years laid the foundations for his DIY attitude and helped set the course for him to ultimately dive headlong into ultra bikepacking and a side quest to create the ultimate vehicle for his adventures.

It all began with sketchy rides in Christchurch’s Port Hills aboard his brother’s Scott Sawtooth MTB, complete with cantilever brakes and slick commuter tyres. “It scared the crap out of me,” says Rufus. His love for the bike quickly took hold: “I started heading up into the hills on my own after school; it started off casually but soon became an obsession, with me riding every single day.”

Cross-country racing (still on his brother’s bike) soon followed, for a time, then the ‘gravity bug’ bit and his focus turned to downhill racing. “I’d saved up enough to get a bike with front suspension (it was bodged together with various Trade Me finds), and that’s roughly the same time I met Joe Nation.

“It’s kind of a full circle for me. When I started riding as a kid, it was just me on my own, riding basic trails for hours on end. I guess it was an escape from unhappy times and became somewhat of a sanctuary. Now that I’m much older, I still associate riding my bike as a safe space to be alone with my thoughts, and although I’m very happy and content with life I still find it valuable as a mental reset.”

Life ticked by, and cycling remained at the centre of Rufus’ life. Working as a mechanic in local bike shops provided a foundation for his love of tinkering and DIY. Late one summer, the shop he was working at as a mechanic folded, and he was cut loose. “I decided if I couldn’t get a job, then I would try and create my own. I had about $5000 saved up and was really lucky to find some room in a warehouse out the back of Addington Coffee Co-op. I set about building a workshop, and by the time I was ready to open, I only had enough money left to stock some tubes; that was it! The first month was tense. I was living off every job that came in, but soon, word got around, and I’d end up working late into the night every night. One thing led to another, and as more work came in, I was able to carry more stock, and things just snowballed.

“After moving the shop a few times as it grew, and taking on more staff, I decided after eight years that it was time for me to get out. I had poured everything into it and was just burnt out. It had grown into a super successful shop with lots of cool brands, but my heart wasn’t in it any more as I started thinking about frame building more and more, so I decided to sell.”

Spending countless days working with bikes sparked Rufus to think about ways in which frames could be better, as well as new ways of thinking about geometry. After he couldn’t find quite what he was looking for in a frame, Rufus set forth to learn how to build precisely what he was searching for. He first put the torch to tube while creating a fixed gear for road riding. The bike served as a mule to figure out how to build a frame and test some geometry theories he had. “I took a night course at CPIT in stainless steel welding, which was the first time I held a torch. It was great to learn the basics and practice, but it was a course very much based on the dairy industry, so it was up to me to figure out some of the tricks to welding much thinner and more complicated joints that you get on a bike. The internet was an amazing resource – as long as you can decipher what is useful and what is not; otherwise, it was just a case of getting stuck in and learning from trial and error.”

Before gravel bikes were an ‘official’ category, Rufus’ second build in 2015 was ahead of its time, based vaguely on a cyclocross bike but with mountain bike-inspired geometry – he retained the drop bars of cyclocross but introduced a dropper post (keep in mind this was 2015!). This bike carried him around his first attempt at Le Petit Brevet, opening the door to bikepack racing and ultra events for him. The frame was quite heavy and eventually met its end after riding countless MTB trails while working as a mechanic on the Enduro World Series circuit for Joe Nation. “It just got absolutely annihilated”.

The Covid lockdown allowed him to refine his designs, resulting in his first CAD-assisted design. A unique build with a suspension fork and clearance for much larger tyres than previous. “I couldn’t order any tubing (over lockdown), so I just used what I had on hand. It was all pretty heavy straight-gauge tubing.” This bike set the direction for his future designs.

The lockdown was also when the seed for the SRMR was planted. “I came across a YouTube video; it blew me away. The landscape, culture and conditions just looked so epic. I wasn’t even into bikepacking at the time but knew that was something I wanted to do one day.”

Emerging from lockdown, he narrowed the focus of his designs and started the journey into his ‘Proto Type’ series, with the quest to engineer the perfect rig for bikepacking under his brand ‘Sufur’.

‘Proto type-1’, the first of his new direction, was in the jig just days before departing for European adventures in 2023, and was finished only hours before heading for the airport. This new bike drew inspiration from his lockdown build. It incorporated a few tweaks to geometry, utilised lighter tubing and was designed to maximise the space for a large frame bag, something Rufus sees as a critical feature. After losing track of gear spread throughout multiple bike bags, “I just wanted to consolidate everything down into one big bag,” crucially saving time by helping keep track of gear while retaining the ability to carry large bottles in the frame. Hiding the bulk of necessary cargo within the frame bag rather than spreading it through multiple bags across the handlebars or saddle has another important spin- off: aerodynamics – helping to save crucial seconds, or even minutes, over thousands of kilometres.

Having put over 12,000km on ‘Proto type-1’, and with tickets booked to the Silk Road Mountain Race, Rufus set to work on ‘Proto type-2’. Building on what he’d already proven as a template for success from ‘Proto type-1,’ he swapped tubing profiles to help tune ride feel, made a few tweaks to the custom 3D-printed junctions, allowing for increased tyre clearance, and adjusted some geometry a touch. “Another thing I considered was how easy it was to fabricate (vs. Type 1) and how accurately I could fabricate a slightly unusual frame shape. This led to a change in some of the junctions and tubing.” Visually, this latest bike doesn’t look noticeably different from its predecessor; it even shares the same purple colour, but the subtle changes mean it is a unique and better riding model.

“3D printing really opens the doors to what is possible with steel frames. You are able to integrate so many features and change your entire workflow with well- designed parts. It’s not easy, though, and doesn’t lend itself to one-off designs because although it can make the fabrication of a frame faster and more accurate, it comes at the cost of a crazy number of hours in CAD.

“The main idea behind this frame was to create something truly specific to bikepacking. I was tired of seeing so many companies take a standard hardtail, braze some bosses to it and call it ‘bikepacking’.”

In typical Rufus tradition, the bike came together just in time – only days before he boarded a flight to SRMR. He’d not even had time for a proper test ride. His first hit-out aboard the new steed was a 4-day shakedown mission on arrival in Kyrgyzstan in an attempt to acclimatise to the altitude before the SRMR flag dropped. “It put a lot more doubts in my mind, for sure.” He mentioned this to Joe Nation, his longtime friend and travel buddy, when discussing the effects of altitude during their recce ride. One thing was sure, though: Rufus knew his new bike was up to the task.

“I signed up for SRMR last November – slowly, over the years, I’d ticked up bigger and bigger events, and without the commitment of having the shop, I figured this was the year! Without a doubt, the toughest part of SRMR was dealing with the altitude; this was new for me with so many passes coming close to 4000m high. It was a real challenge to keep pushing at those heights when you’re lugging a loaded bike and often under-fuelled or dehydrated. I can’t express just how exhausted and dizzy you get at the top of the passes, but as soon as you drop back down to a normal height, you’re completely fine again. Getting a little overambitious about what I could do in a day would often mean I would have to sleep at altitude, which is terrible when you’re trying to recover for the next day.”

“On the evening of day four, I was rapidly struck by a bug. I was pushing up the Old Soviet Road out of checkpoint two, feeling fine, and within the space of about 15 – 20 minutes I was reduced to a curled-up mess on the ground. I was a little freaked out as I didn’t know how bad it was going to get, and I was all out of water. All I could do was pop some medicine, unravel my sleeping gear and wait it out. It was a super rough night stuck on a ridge at 3500m. Luckily, I only had some light rain overnight, as some pretty big storms can kick up in the evenings. After about nine hours, I felt a bit more like myself and decided to move on so I could find a river to filter some water out of.

“I had a pretty special moment on the morning of the sixth day. For days, Marin de Saint-Exupéry, Ron van Roosmalen and I had been constantly jostling for third position. We had all slept relatively close to each other the night before, but with no reception available, none of us knew. That morning, I packed up and within an hour rolled into a notorious junction where there is a cafe open 24 hours. Inside, I found Marin with about three plates of food laid out in front of him. I joined his table, and within a few minutes, Ron arrived too! For a moment, we all enjoyed some breakfast together while sharing stories, then Ron announced that he had proposed to his girlfriend at Checkpoint 3! It was a brief but very enjoyable moment – although we were all battling for the same position, there was nothing but respect for one another.”

“I find it hard to put Kyrgyzstan into words; there’s just so much going on, and it’s all very foreign to what we’re used to in NZ. The people are amazing; everyone wants to talk, shake your hand, or share a meal with you. Spotting somewhere to eat can be a challenge as there’s never any signage. You just have to “know”. When you find somewhere, it’s always hard to tell if it’s actually a food caravan or if someone has just invited you into their home. You get sat down, and with the language being a bit of a barrier, you have no idea what’s coming. They just start bringing food. It’s usually some kind of stew with bread and lots of chai tea. There is an odd culture of staying up late and sleeping in late. Sometimes, I’d roll through a village at 1am, and there would be a group of kids playing football. The next day, some shops wouldn’t open till 10am.”

Given Rufus and Joe have been friends and competitors for over 20 years, have travelled the world together, and now share epic bikepacking adventures, it was only fitting we got Joe’s lens on his mate Rufus: “I’d say the key with Rufus is that he’s not fussy. I saw him in 2008, living in the bush in Morzine, day after day, dividing up cold cans of ravioli into breakfast, lunch and tea-sized portions, just cold. All he’d eat in a day is just one can of ravioli for, I don’t know, 50 Euro cents or something at the time, not complaining though.

“He never gives up. There are not many people behind me at a bikepacking race that I’d be more worried about than Rufus. I know that no matter what, you know, darkness or storms or how gnarly a pass is, he’s not really going to slow down. It’s going to take something a lot more than that, so yeah, he just doesn’t give up.

“I think we’ve helped each other out in terms of progressing in this ultra-distance stuff, and in the first place, I wouldn’t be doing it without him. He was the first one to talk me into attempting the Petit Brevet back in maybe 2015, so there’s no way I would have been into this sort of stuff without his influence. Years later, I convinced him to join me for the Great British Divide, so we’ve helped each other out – and it’s bloody useful having a local guy too, you know, we just push each other.”

With SRMR behind him and his body slowly on the rebound, Rufus has set his sights on his next challenge: developing and building more bikes for his growing base of fans. Needless to say, some time in the coming months, he’ll be hurriedly welding up another bike and heading to a start line somewhere.